Workplace health can change! The story of tobacco control

09 Nov 16 |

By Shelia Duffy, Chief Executive at ASH Scotland

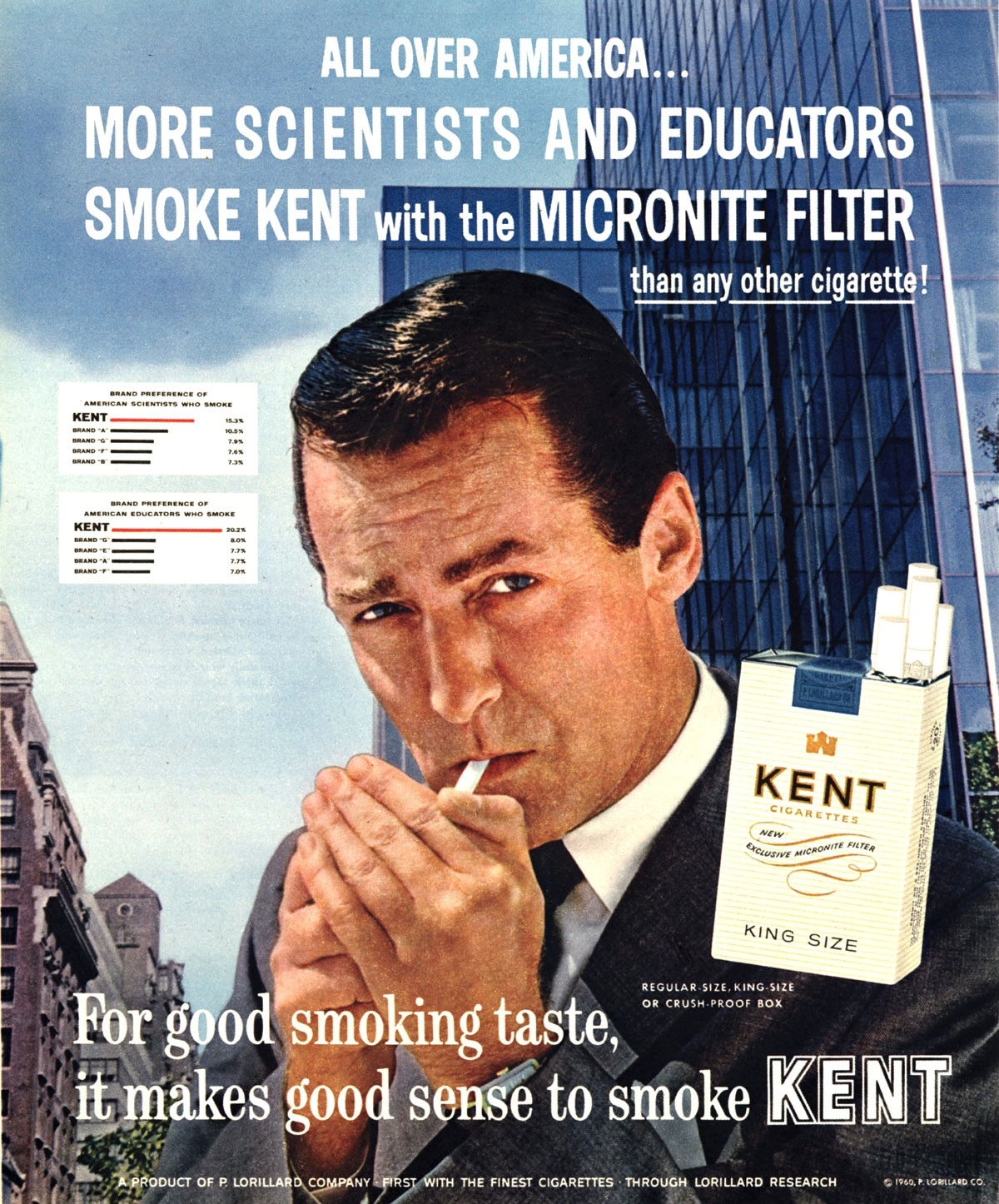

This year, Scotland celebrated a decade of smoke-free enclosed public spaces. To borrow a thought from Virginia Slims, we’ve come a long way, baby. And we’re now quite a long way from the widespread normality and visibility of smoking in past decades, where physicians smoked while attending patients, and workplaces were often thick with smoke.

Like any progress in regulating tobacco, smoke-free laws took time. During the 1980s the evidence mounted steadily, although forcibly denied by tobacco companies. After a voluntary approach delivered increased signage but no real protection, we and others began to push hard for legislation. The establishment of a Scottish Parliament with the power to pass health laws provided momentum, but it still took five or six years for press and public opinion to swing from indifference and hostility to a firm backing for the measure that led to Scotland becoming a world-wide pioneer of smoke-free. It was that awareness and support – forged in the heat of public debate – which led to the highly successful implementation of one of our Parliament’s most popular measures.

The benefits began to show quickly. Bar workers showed significant improvements in respiratory symptoms and lung function within a few months, and reported fewer chest and throat problems.

A study of nine Scottish hospitals found a 17% fall in admissions for heart attacks in the first year after smoke-free legislation came into force. [1] Further research demonstrated an 18% reduction in child asthma admissions to hospital (reversing a previous trend showing a 5% increase per year in the years preceding the law). There was a marked decline in stroke admissions. Importantly, public support for the measure was high, and became higher once implemented. A majority of smokers supported it. And the fears that smoking would be driven into domestic settings, exposing children to greater harms, failed to materialise. Instead, more families introduced smoke-free restrictions.

The recently published Scottish Health Survey suggests that children’s reported exposure to tobacco fell dramatically from 11% to 6% – possibly due to two years of the excellent ‘Take it Right Outside’ mass media campaign. From December 5th 2016 the legislation prohibiting smoking in cars with under 18s present comes into force, preceded by a mass media awareness raising campaign. In 2017 we will see a debate around regulations extending the smoke-free legislation in hospital buildings to cover an outside perimeter, removing smokedrift from windows and doorways.

Today’s main challenge is to level the playing field for our poorest communities, where smoking rates are still high and cigarettes still a normal feature of life. If attitudes and culture can change in these communities, we will go a long way towards improving the health of the next generation, and putting smoking out of sight and out of fashion for our children.

- Pell JP et al (2008) Smoke-free legislation and hospitalizations for acute coronary syndrome NEJM 359 (5) 482-91

This article was originally published in The SCPN Newsletter Volume 7, Issue 4. Read the digital newsletter below using Issuu, or feel free to download the PDF.

View the PDF

The SCPN Newsletter: Volume 7, Issue 4

Our final newsletter of 2016 contains something a little different for us - a themed issue on workplace health. We cover public awareness of obesity as a risk for cancer, how workplace health has improved with the story of tobacco control and, implementing behaviour change in GP Practices.